Lessons from Houston and Harris County after Hurricane Harvey

Houston, Texas has seen flooding since the city was founded in 1836. Property damages from flooding in 1929 alone eclipsed $1 million, an extraordinary cost at the time. In 1935, flooding so severely damaged the Port of Houston that it was nearly inoperable for months. Today, Harris County (where Houston is the county seat) sees a major flood every two years. In 2017, when Hurricane Harvey hit Southeast Texas, it led to over 100 deaths and caused an estimated $125 billion in damages, making it the deadliest hurricane to hit Texas in nearly 100 years.

Hurricane Harvey is just one event within the larger story of stronger storms and more frequent flooding in Texas in recent years—but the scale of devastation was a call to action. In Harvey’s aftermath, communities across Southeast Texas are stepping up their preparation for the next disaster. This article highlights two municipalities in Southeast Texas—the City of Houston and Harris County—as they respond to the realities of increased flooding. As local leaders across the country face similar challenges, they can learn from the Houston area’s flood journey. This article highlights some key themes of their story:

- The 100-year and 500-year floods as key concepts

- How Houston, Harris County, and other communities across the country are reframing their approaches to new construction to be more responsive to the realities of increasing flood risk

- How the community came together in support of a $2.5 billion investment in projects to reduce future flood impacts

- How new rainfall data is increasing flood risk estimates, further shaping the Houston area’s efforts to adapt

Defining the 100-year and 500-year floods

To better understand Houston’s story and that of many other flood-prone communities across the United States, it’s important to first define the concepts of 100-year and 500-year floods, floodplains, and flood elevations.

- Floodplains are defined by the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) as any land area that is prone to being covered by floodwaters from any source. Within a floodplain, there are many different levels of flood risk.

- Flood risk is defined by the percentage-chance of a large flood happening in a given year. FEMA defines two major levels of flood risk, often used for local regulations: the 100-year flood, and the 500-year flood.

- A 100-year flood is a large flood that has a 1 in 100 or 1% chance of happening in a given year, and a 26% chance of flooding at least once over the life of a 30-year mortgage. The area that its floodwaters may cover is the 100-year floodplain, and the height that its waters may reach is the 100-year flood elevation. In Houston, this height is also known as the base flood elevation.

- A 500-year flood is an even bigger flood, but expected to happen less frequently than a 100-year flood. A 500-year flood has a 1 in 500 or 0.2% chance of happening in a given year, and a 6% chance of flooding at least once over the life of a 30-year mortgage. The area that its floodwaters may cover is the 500-year floodplain, and the height that its waters may reach is the 500-year flood elevation.

As storms become stronger and sea levels continue to rise, flood maps in many parts of the country have not kept up with the increasing risk. In fact, a June 2020 report from the First Street Foundation found that nearly 6 million households in the contiguous U.S. may not be aware of their flood risk due to an underrepresentation of risk by federal flood maps. To learn more about federal flood maps and the challenges communities face with outdated maps, read our article on this topic.

Houston and Harris County respond to risks with construction updates

With billions of dollars in damages after Hurricane Harvey, local leaders in Houston and Harris County saw the need for change, weighed options for action, and ultimately reframed their standards for new construction to be more responsive to the realities of increasing flood risk.

The need for change: The City of Houston led a post-Harvey report assessing the need for, and feasibility of, making newly constructed or renovated buildings more flood-ready. Here are some key points from the report:

- Homes with less perceived risk still suffered. The report found that the majority of homes impacted by flooding from Harvey were located outside of the 100-year floodplain, indicating that Houston’s pre-Harvey floodplain regulations, which applied only to properties within the 100-year floodplain, were inadequate.

- New construction should adapt to increased flood risk. The report proposed new standards for elevating newly constructed or significantly renovated buildings higher above the ground to prevent damage from future floods.

- The benefits of lifting new construction could outweigh costs. The report found that the proposed new standards could result in higher development costs, but also potential savings from avoided damages.

- The new standards could increase costs for newly constructed homes by an estimated $11,000 to $32,000 per home, but they could reduce future flood damages, which cost $56,000 per home on average after Harvey.

New standards: Less than a year after Hurricane Harvey, both Houston and Harris County updated their floodplain regulations to include new standards for construction, including some key changes:

- Expand the area to which flood-ready standards apply. Before Harvey, Houston’s flood-related construction standards applied to properties within the 100-year floodplain—now, the 500-year floodplain is also included, meaning that more properties across a larger area will be expected to comply.

- Going beyond the mapped floodplain. Harris County now requires that new construction outside of the 500-year floodplain be lifted to a height of 1 foot above the nearest ground or street surface. This update shows that Harris County recognizes flooding can happen anywhere, even outside the floodplain designated by FEMA maps.

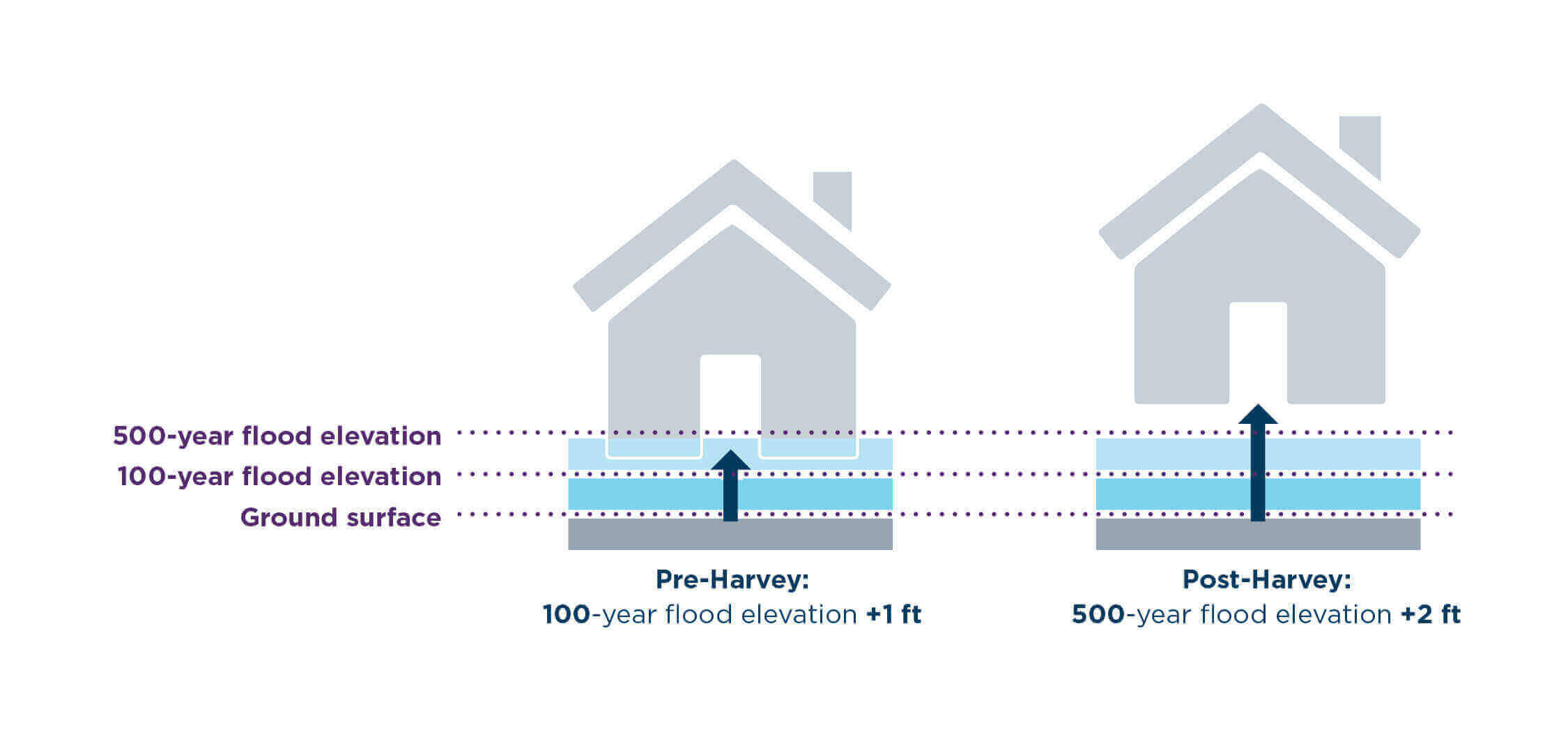

- Elevate new construction. The diagram below shows how Houston’s building elevation standards have changed. Both Houston and Harris County now require new or significantly renovated buildings to be elevated to 2 feet above the 500-year flood elevation. An estimated 90% of homes that flooded during Harvey would have avoided flood damages if they had been constructed in this way.

Community concerns: The updated floodplain regulations are still very new, and some community members and groups have expressed reservations about their effectiveness. Key concerns include:

- Financial burdens and disproportionate impacts on low-income neighborhoods. Houston’s median household income of $47,000 means that many homeowners cannot afford additional development costs

- Slow implementation, especially for older properties, since the regulations apply only to new construction or to major renovations

- A false sense of security, since the new standards rely on compliance from the owners and builders of new construction projects, in order to result in reducing the risk of damage from future floods

Construction takeaways for local leaders: Local leaders in other flood-prone communities can consider the following takeaways from the Houston area’s process for strengthening standards for flood-ready construction:

- Point to stronger storms to build urgency and encourage action. As the third 500-year storm in three years, Hurricane Harvey created the sense of urgency needed for the government to act.

- Gather data about the costs of flood damage. Data from Hurricane Harvey allowed local leaders to estimate costs from future floods, and to inform updates to regulations, with the goal of saving money in the long run.

- Get input from a diverse group of stakeholders to assess adaptation actions. Houston held public comment periods and sought input from community leaders about the proposed updates.

Construction updates across the county

Like Houston and Harris County, many communities across the U.S. are requiring new construction to be more responsive to flooding–with notable examples listed below. These actions not only strengthen adaptation to flooding, but may also count as credits to reduce flood insurance premiums for residents via FEMA’s Community Rating System (CRS). By voluntarily participating in CRS, communities can reduce flood insurance premiums by 5% to 45%, depending on the number of credits awarded.

In cities like Norfolk, VA, Cedar Falls, IA, and Baltimore, MD, local leaders have proactively implemented standards that require construction to be elevated above specific flood elevations. Tulsa, OK is another example of a community going beyond federal standards and limiting development in flood-prone areas. Measures like these can better prepare the community and residents against flooding threats.

Harris County residents invest $2.5 billion in adaptation

Hurricane Harvey forced a change in the Houston region, not only for construction standards but also for the scale of financing. Almost one year to the day after Harvey made landfall, nearly 85% of residents in Harris County voted to approve a $2.5 billion bond to support projects for reducing the impacts of future floods. Since the bond passed, the Harris County Flood Control District announced that 70% of drainage system repairs due to Harvey are complete, and over 500 homes have been bought out. As the largest flood-focused investment that Harris County has ever made, the bond includes funding for:

- $1.2 billion for channel conveyance improvements to help floodwaters flow away from developed areas

- $400 million for stormwater detention basins to store and slow floodwaters

- $242 million for land acquisition to reduce flood damage to buildings by maximizing open space in areas of high flood risk

- $12.5 million for floodplain mapping to improve maps in the Houston area that have not been updated in nearly 20 years

- $1.25 million for a flood warning system to help residents get out of harm’s way during a flood

Low-income communities are often hardest hit by floods and take the longest time to recover, as was the case in Houston post-Harvey. Recognizing that disaster recovery and relief is often not equitable, Harris County included an equity provision in its 2018 bond. In 2019, the County passed a resolution to further ensure an equitable recovery. The Harris Thrives Resolution—advanced by the Coalition for Environment, Equity, and Resilience, Houston Organizing Movement for Equity, and others—requires expanded community representation in oversight of the bond, and expanded consideration of equity in project prioritization through the use of a Social Vulnerability Index (SVI). The SVI includes many variables from census data such as age, disability, and socioeconomic status. Local leaders can use the SVI to identify areas where residents may need extra support in preparing for or recovering from floods.

More rain, more risk: Atlas 14

On top of the devastation caused by Hurricane Harvey and other recent floods, new rainfall data, known as Atlas 14, created an added call to action for local leaders in the Houston area. The first update of its kind in 58 years, this statewide data on rainfall intensity and frequency shows that Texas is already receiving more rainfall than was previously estimated.

Impacts of the new data: The new Atlas 14 data, released in 2018 by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), has further shaped the Houston area’s approach to flooding. Here are some key impacts of the data:

- Mapped floodplains may grow. The data is expected to affect how floodplains are redrawn. With preliminary floodplain map updates planned for late 2021, the new data will likely result in larger 100-year and 500-year floodplains.

- Bigger pipes, pumps, and drainage areas. In response to the new data, Harris County redefined the 100-year storm, a key metric used for stormwater management and infrastructure design, to include nearly 40% more rainfall in a 24-hour period. This means that engineers and designers must now design drainage areas, pipes, and pumps to handle much more rainfall.

- More water storage. Stronger standards for water storage in Houston and Harris County will help newly developed properties to hold more stormwater on-site, preventing water from spilling onto neighboring properties, streets, and infrastructure. Examples of these standards include:

- Increasing the storage capacity of ponds, and other areas used to store water from storms, by 20%– resulting in about 32,500 gallons of added water storage per acre.

- Requiring any fill (like earth or gravel) added to a construction site in the floodplain to be balanced with the removal of an equal amount of fill. Known as the zero net fill rule, this allows as much water to be stored on the site as would have been possible prior to development.

Atlas 14 takeaways for local leaders: Local leaders in other flood-prone communities can consider some key takeaways from the Houston area’s efforts to keep pace with increased rainfall:

- Your Atlas 14 data. NOAA periodically updates Atlas 14 data for nearly every part of the U.S. Find out when your state was last updated by visiting NOAA’s website.

- Point to new data as a driver for change. With data showing more rainfall amounts, local leaders were able to push for updates to floodplain maps and stormwater management standards, and used this data to increase the sense of urgency already created by Hurricane Harvey and other recent floods.

- Emphasize benefits to neighbors and neighborhoods. Local leaders can tell the story of stormwater management in terms of its impacts on people. In the Houston area, storing more water on each newly developed property can prevent further flooding on neighboring properties and streets, and can ultimately prevent drainage systems that serve entire neighborhoods from becoming overwhelmed during large storms.

The stormwater management standards described above are only a sample of the full extent of changes underway in the Houston area in response to the new Atlas 14 data and recent flood impacts. To learn more about the interim guidelines outlined by Harris County, see the 2019 Atlas 14 Policy Criteria and Procedures Manual.

Conclusion

Over the past several years, Houston, Harris County, and communities across the country have taken major steps in adapting to stronger storms, rising sea levels, and more frequent flooding. These actions take many different forms, often requiring creativity, collaboration, and extensive planning.

Each community is different, with its own unique needs and challenges— and the actions described in this article only scratch the surface of the full range of steps local communities can take to reduce the impacts of flooding. From Houston to Baltimore, Tulsa to Cedar Falls and beyond, municipalities of all sizes are leading the way to update standards and invest in their communities to be better prepared for more flooding and stronger storms.

Want to view the full version of this resource? Join the American Flood Coalition by visiting our website.

This post was authored by Liz Cassin, Senior Outreach Associate.