April 26, 2022

—

Charleston, South Carolina, has the largest historic district in the nation, essential to the nation’s culture and the city’s beauty, economy and livelihood.

But Charleston is also one of the country’s most flood-prone cities. And with a booming population and infrastructure dating back hundreds of years, solutions to keep downtown, as well as the rest of the city, above water are increasingly urgent and challenging.

That’s why in 2017, Charleston added the position of chief resilience officer to lead efforts to address flooding and sea level rise. To better understand these challenges and the importance of such a position, we spoke with Charleston’s Chief Resilience Officer Dale Morris, who has held the position since September 2021.

Morris has an extensive background on resilience and water management. Prior to coming to Charleston, Morris was at The Water Institute of the Gulf, a technical research nonprofit. Before that, he coordinated the Dutch Government’s flood and adaptation work in the U.S.

He is also the co-founder of the Dutch Dialogues, a flood resilience workshop model used in several cities, including Charleston. The American Flood Coalition helped fund the Dutch Dialogues Charleston and participated in the forum.

The following interview has been edited for length and clarity.

American Flood Coalition: What’s a chief resilience officer (CRO) and what’s their responsibility?

Dale Morris: The standard 100 Resilient Cities’ definition of resilience is the ability to respond to, manage, and recover from shocks and stresses. Generally, the CRO’s job is to break down silos within city government, and then serve as an access point for stakeholders — whether it’s individual citizens or groups — to share their thoughts with the local government and to think more about what resilience is and how the city can achieve it. I can be the lightning rod, or I can be the provocateur with the stakeholders about those issues.

AFC: When it comes to flooding and sea level rise, what role does the CRO play in Charleston?

DM: That is my number one issue. I wish I had more time to do things on heat and maybe economic resilience, but community flood resilience is most of it. I sit in the mayor’s department, and we work across departments — storm water management, public services, building inspections, transportation, planning — to build resilience.

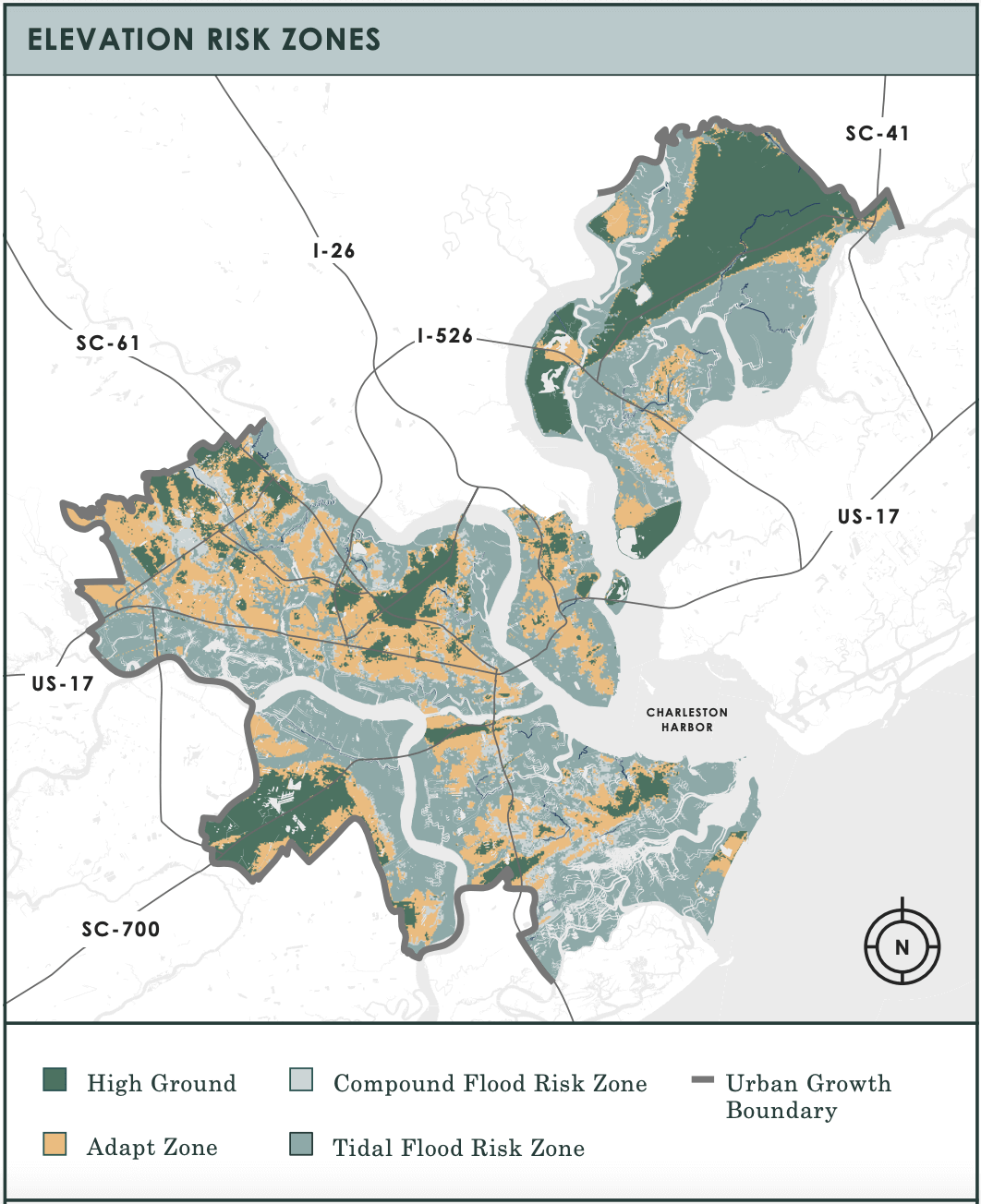

We have a newly adopted Comprehensive Plan in the city, with water as our primary organizing principle. Our water risk, flood risks, and adaptation opportunities all guide this plan. And we have land-use recommendations to conserve and protect a number of areas, like marsh or low-lying areas, from development.

AFC: How does one become a CRO?

DM: I don’t think there’s a standard template. There is a diversity of folks, of people who were from within government and from outside of government who assume these CRO positions, who are often the most passionate, the most knowledgeable about resilience, who then drive change.

The former chief resilience officer was going to retire and told me he thought I’d be great for this job. And because I had a lot of experience with the Army Corps of Engineers and flood risk mitigation and adaptation, I thought I could probably do this. I’m not a planner, not a stormwater manager, not an engineer. But I do have a breadth of experience.

AFC: Are there any parts about the job that kind of keep you up at night?

DM: Like most cities, we don’t have enough capacity, people, and money to do everything we need to do. So, we have priorities. But I do worry about the longer-term ability for us to do everything well. A storm surge or a bad tidal flood would be very disruptive for parts of the community and geography. We have the largest historic district in the nation. It’s worth protecting. But the risk never gets to zero. So, do we have the resources sufficient for this challenge? I think for most coastal cities, the answer is no.

AFC: Have you connected with other cities facing flooding and sea level rise to share best practices or learn from each other?

DM: We are part of the Resilient Cities Network, and we’re in a North America climate program with them. And that program is five cities collaborating more or less on environmental justice or social justice issues within the context of resilience and flooding: Boston, Houston, Chicago, New Orleans, and Charleston.

We also have a side network of cities that are in a coastal storm management project with the Army Corps of Engineers. And we get together and compare notes and share frustrations and share good news. And that is New York, Norfolk, Miami, Jacksonville. Just through good fortune and my past experience, I also know a number of chief resilience officers: Mobile, Jacksonville, New Orleans, Houston, Pittsburgh, Miami Dade. It’s a network, and we need each other.

AFC: What projects is Charleston working on that you’re excited about?

DM: We are excited about getting into the design phase with the Army Corps of Engineers on a seawall project — to make this thing attractive, multi-functional, to mitigate the surge risk in a way that is acceptable to the city. And that project has a benefit-cost ratio of 10.8, the highest in the nation.

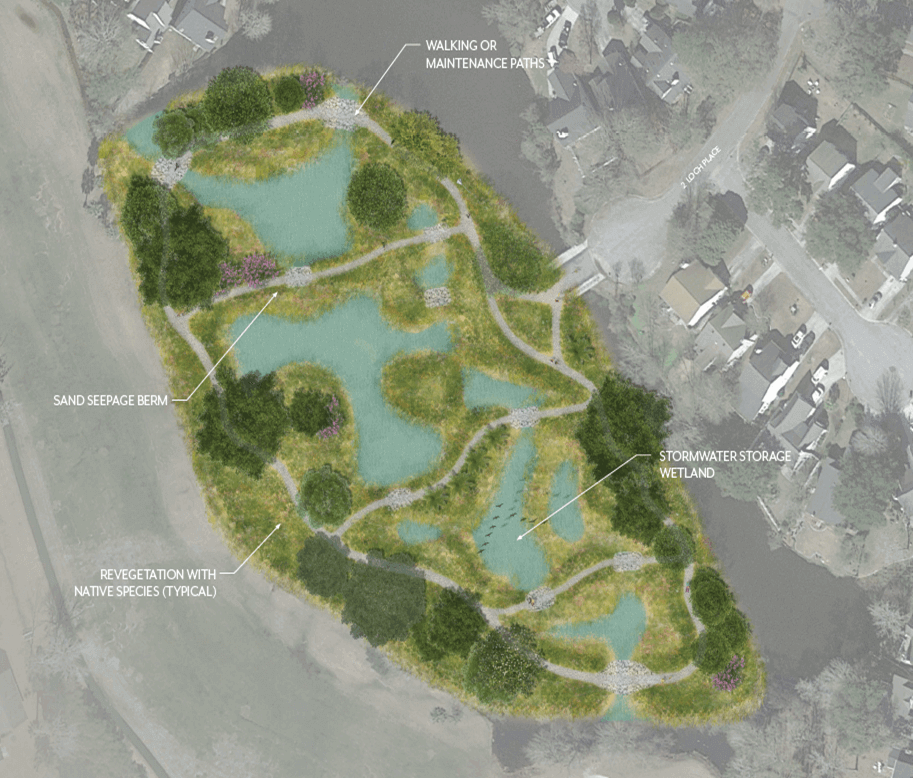

We also have a project in the Church Creek Basin, where 32 homes were bought out because of repetitive flood loss. It’s in a subdivision built mostly ’50s and ’60s on constricted tidal creek channels [an area where a creek gets narrower and creates a bottleneck]. So, we’re adding a biozone, restoring the pre-development condition, and making it a storm water management feature, as well as a park. When it rains hard and the basin swells up, water will be diverted into the biozone and store that water until the tide goes down.

So, it’s not just gray infrastructure — it’s gray and green, it’s zoning, it’s using the carrots and the sticks with developers. It’s all of the above.

AFC: Is there anything we haven’t covered?

DM: One thing is the issue of recency bias, which is our tendency to worry about and plan for the most recent disaster. This is understandable but is, in fact, backward-looking, and we should be forward-oriented. We have had a number of rain bombs here and some tidal impacts, but those aren’t the only risks we have.

So, how do we manage them together while acknowledging people’s recency bias? At an individual, policy, and governance level, we have to guard against that. We have to deal with all of the risks and impacts and not just allow the last event to have our attention.

—

Featured image at top: Charleston, South Carolina waterfront. Credit: Simon/Flickr