February 6, 2023

—

When communities face a disaster, one position is in the thick of it: emergency managers.

Emergency managers are responsible for coordinating response and recovery, as well as preparing communities before disaster strikes. Over the years, this position has evolved, incorporating the latest research and disaster science. Emergency managers also ensure that the most vulnerable populations, usually disproportionately affected by disasters, are equitably served.

“Most emergency managers are excellent trainers and project managers, but they’re also very good at community program implementation, community engagement, and outreach,” said Chauncia Willis, who has been a professional emergency manager for over 23 years.

Willis is a senior advisor with the American Flood Coalition, where she offers expertise on the intersection of emergency management and social equity issues, and the CEO and founder of the Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management (I-DIEM), which strives to empower marginalized communities within all phases of the disaster management cycle.

“As an organization, we’re advising emergency managers to understand the history of the community, the challenges, who is most vulnerable, and why they’re most vulnerable,” said Willis. “If you keep ignoring the most vulnerable communities, you are decreasing their ability to become resilient.”

In her role as an AFC senior advisor, Willis worked on our report, Conversations with Communities: Considerations for Equitable Flooding and Disaster Recovery Policy, a joint project with Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management, and advised on AFC resources Turning the Tide: Opportunities to Build Social Equity through Federal Flood Disaster Policy and Dual Disaster Handbook: 6 Recommendations for Local Leaders Responding to Floods during COVID-19.

Willis got into emergency management after experiencing firsthand a hurricane that struck New Orleans while she was an undergraduate student at Loyala University New Orleans. Willis was able to evacuate the city with friends, but only after she pulled together enough money for a hotel and spent hours on the highway.

Her experience highlighted the barriers that people can face in a crisis — and how only some can afford to evacuate in case of an emergency.

Much of Willis’s career is shaped by her life as a Black woman. Historically, many emergency managers are white men who are often retired military or law enforcement officers. But that profile rarely represents the diverse communities who need resources after a disaster strikes.

“Unfortunately, what happens during a disaster is that those who are not intimately connected to a white male suffer disproportionately, but also repetitively,” said Willis. “You see the suffering that it causes when there’s not diverse representation, because the people in leadership are the ones that are developing the policy — they’re deciding who gets money invested into their community to be more prepared for a disaster.”

Discrimination can further prevent these vulnerable communities — often disproportionately low-income and people of color — from receiving much-needed aid. In responding to Hurricane Katrina, Willis recounted a time when she overheard one of white male workers speculate that those receiving aid would spend it on alcohol.

“I thought, ‘Wait a minute. You’re supposed to be going to respond and help, but you don’t even like the people,’” she said. “When you diversify, and offer a different perspective, and you actually represent the people that are being served, you are creating equity.”

Often, emergency managers haven’t been trained on equity, or the history of inequity and how it still exists through historical barriers, such as redlining.

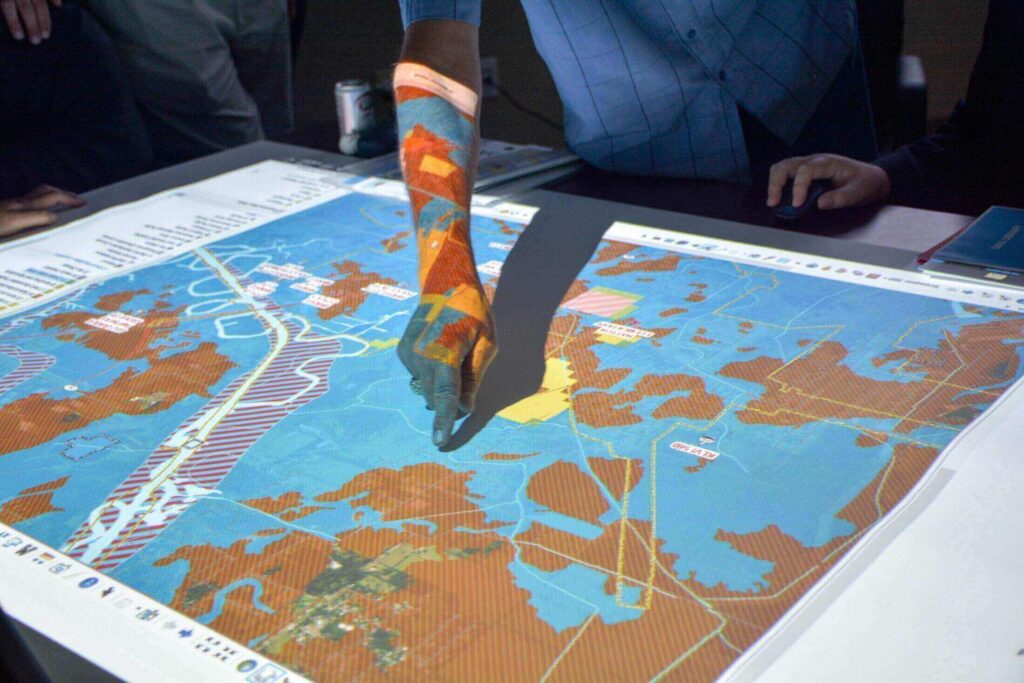

The Institute for Diversity and Inclusion in Emergency Management hopes to change this by instilling a human-centered approach to emergency management, both through educating about this history — such as why certain communities face repetitive flooding — and helping emergency managers conduct vulnerability assessments to reverse and avoid exacerbating such trends.

“Why am I so passionate about this? Because I live it,” said Willis. “I understand what the communities are saying. And in many cases, we will take that perspective to the federal agencies, so they can prioritize the creation of equitable solutions.”