December 6, 2021

—

Stronger storms and rising sea levels are threatening people across the country. As communities prepare for and respond to such events, however, one impact is often overlooked: how flooding affects long-term public health.

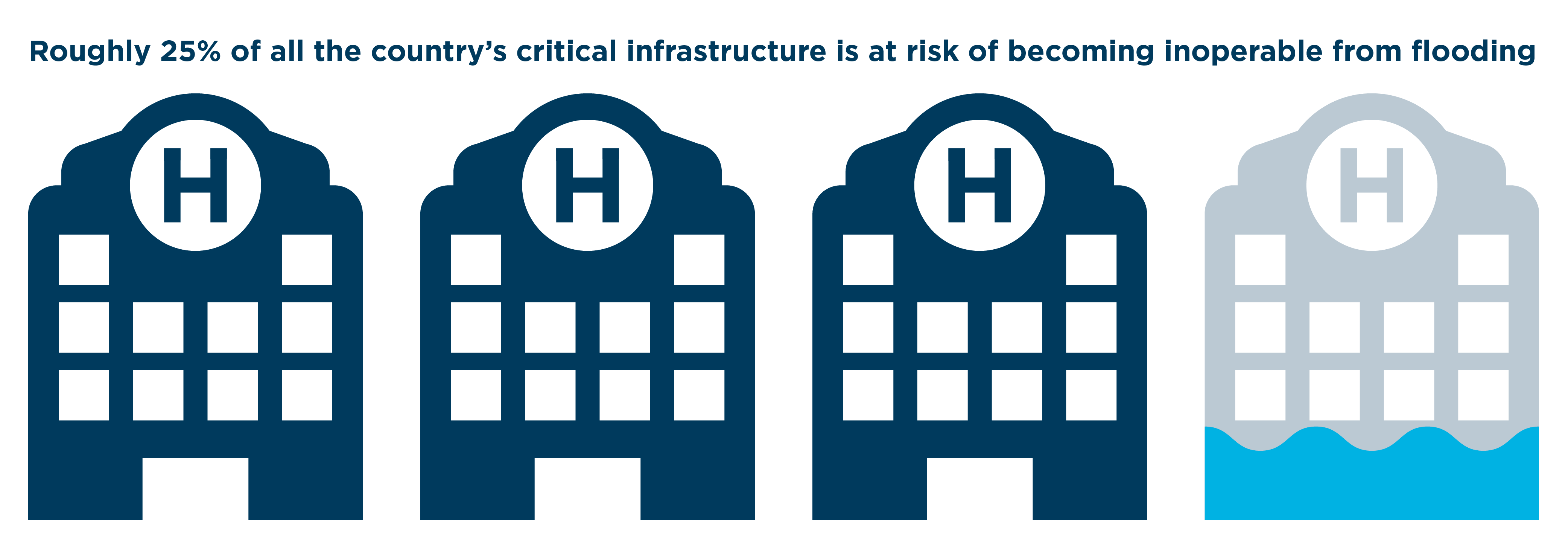

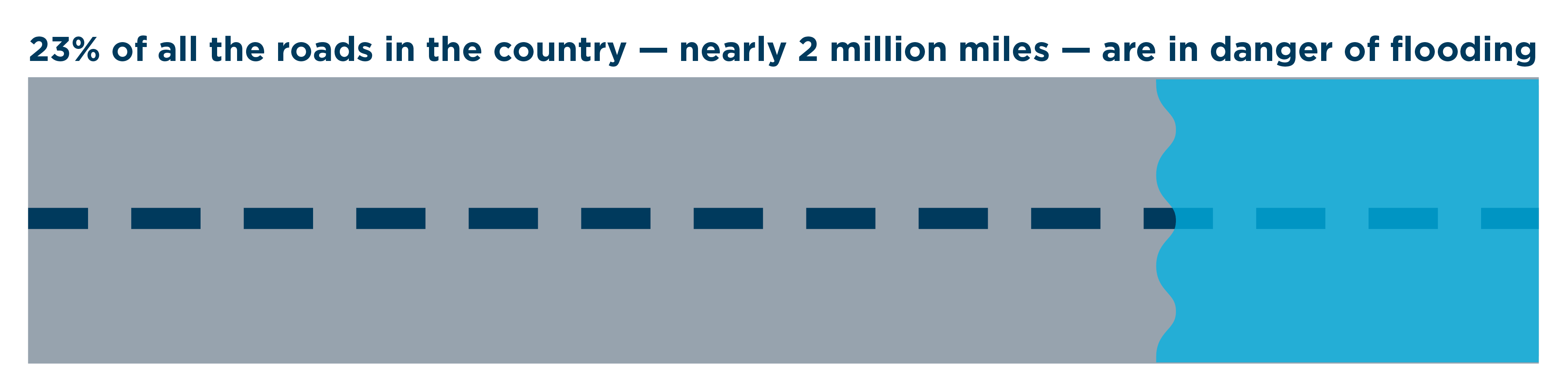

A recent First Street Foundation report finds that roughly 25% of the country’s critical infrastructure, including public safety services, are currently at risk of becoming inoperable due to flooding. Additionally, 23% of the country’s roads, nearly two million miles, are currently in danger of flooding.

Given damaged public health infrastructure, alongside contaminated floodwaters, injuries, and disease, a single flood can overwhelm communities’ healthcare systems and cause long-term health crises.

But in the face of these impacts, communities are not powerless. This post explores ways that flooding threatens public health and how leaders and residents can prepare for these risks to create safer, more resilient communities.

Public health risks

With everything that floods can cause — evacuations, power outages, long-term recoveries — public health risks may not be at the top of minds for flood-prone communities. But given the wide-ranging health impacts of severe storms, communities must consider how flooding affects public health.

Damage to hospitals and other health infrastructure

Flooding can damage critical public health infrastructure, like hospitals and nursing homes. In 2012, water from Superstorm Sandy rushed into Coney Island Hospital, shutting off electricity and emergency power. The hospital was forced to close for three months and divert its patients to other hospitals, many of which were also damaged by the storm.

Even if hospitals remain open, submerged roads and downed cell phone towers and telephone lines can impede access to healthcare facilities for days, weeks, or even months. According to an after-action report by the Texas Hospital Association, Hurricane Harvey closed roads, slowing supply deliveries to hospitals and preventing some dialysis patients from receiving treatment.

Since people living in flood plains are disproportionately from low-income backgrounds, infrastructure that is inaccessible may lead to long-term health disparities. When Harvey hit Texas, Lyndon B. Johnson General Hospital, which provides care for much of the economically disadvantaged northeast Houston, had to close more than half of its 200 inpatient beds for several months.

Ongoing public health emergencies, such as COVID-19 or the opioid epidemic, can further strain hospitals, many of which are already overwhelmed with patients.

Contaminated environments

Severe storms and heavy rainfall can also leave behind another problem: polluted land, air, and water. Harvey flooded or damaged at least 13 Superfund sites, sending cancer-causing chemicals into the low-income, minority communities surrounding those sites.

Floodwaters can also pick up contaminants like animal waste, fertilizers, and oil, before emptying into reservoirs or rivers or sinking into wells. This creates a long-lasting problem, even after flood waters recede: Contaminants can sink into houses and the ground, going undetected for months and giving people a false sense of safety.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, contaminated flood water can cause wound infections, skin rashes, gastrointestinal illness, tetanus, and in rare cases, a bacterial infection called leptospirosis. After Harvey, several people died from flesh-eating bacteria, which can live in floodwaters and enter through a wound or cut.

Solutions

Communities with the right preparation and mindset can avoid some of the worst public health risks associated with flooding. For some solutions, communities and leaders can turn to existing resources by the American Flood Coalition and its partners.

Protect critical infrastructure

Facing flooding disasters, communities must protect facilities that are essential to a community’s health and safety, such as healthcare facilities and wastewater treatment plants. First Street Foundation’s Flood Factor allows communities to calculate and understand flood risk for critical infrastructure.

With this information, municipalities can start protecting their infrastructure. For example, planners in AFC member city St. Augustine, Florida, surrounded a wastewater plant with portable flood barriers, which can be quickly installed ahead of a storm. In Boston, city planners built the Spaulding Rehabilitation Center, a critical health facility on the coast, 30 inches above the 500-year floodplain.

For more ideas, check out AFC’s Adaptation for All guide, which helps local leaders find flood-protection approaches that can work best for them.

Update maps to reflect public health risk

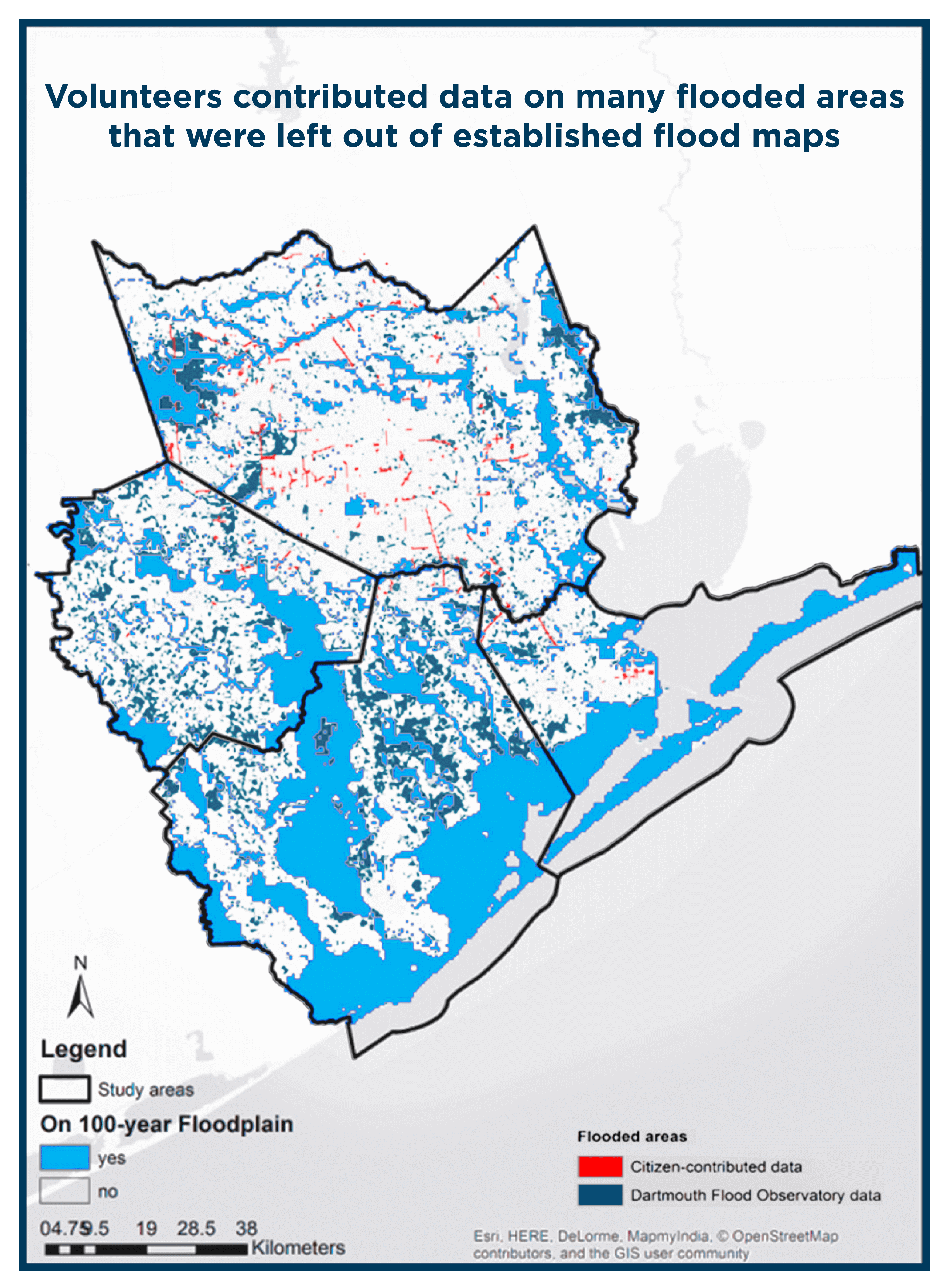

When it comes to flooding, many properties are outside of FEMA’s existing flood maps, which are often outdated and fail to account for factors like sea level rise. Because of this, many homeowners — and utilities operators — underestimate risk, or feel like there’s no risk at all, leaving them vastly unprepared when disasters strike.

For example, Harvey flooded acres of parks and properties in Houston, even though they were outside the floodplains mapped out by FEMA. Responding to this disaster, volunteers collected data on flooded areas and uploaded it to an online map. The data gave first responders real-time flood information about 57 square miles of flooded area that was excluded on established flood maps.

Flood maps should also be overlaid with public health maps, which let governments identify and assist people who have health problems and are at risk from flooding, such as those who are elderly, homeless, isolated, or on power-dependent medical equipment. Such information can help target warning messages before extreme weather events, locate unstable infrastructure that may collapse from flooding, and support emergency responders during a disaster.

Ensure flood response and preparation considers public health

As communities of every size address challenges from flooding, they must also address the public health risks that inevitably come from these disasters. For example, Charleston, South Carolina, recently received money to improve stormwater drainage in its downtown medical district.

The COVID-19 pandemic highlights the importance of considering both flooding and public health. Without proper preparation, hospitals using resources to treat COVID-19 patients may be unequipped to handle the added stress of a severe storm or flood. Temporary shelters or evacuation centers may also be difficult to set up while complying with physical distancing.

Part of this preparation includes educating the public about dangers of wading into flood water. Elected officials and community leaders have a responsibility to incorporate public health considerations in their messages around flooding.

Our Dual Disaster Handbook has six actionable recommendations for planning a proactive response as communities face multiple threats this season.

—

Though sometimes overlooked, public health should be a key part of any community’s flood preparation, response, and recovery. We can do this by ensuring much of our existing flood work complements public health efforts, using many resources that already exist, and educating the general public.

Overall, communities must recognize the lasting damage floods can have on public health. Though we can rebuild much infrastructure, we can never get back lives lost.

This post was authored by Brandon Pytel, Communications Associate, and Gian Tavares, Senior Strategy Associate.